By Matt Lammers and Andy Fein, luthier at Fein Violins

116 years ago on May 20, 1896, Paris newspapers were filled with news of an incident that left the French arts culture reeling. At exactly 8:57 p.m., during a performance of the opera Helle', two 360 kg (about 792 lbs. each) counterweights fell from the chandelier above the audience, which killed one spectator and injured many others.

The chandelier and bronze reflector behind the chandelier were supported by a system of counterweights that insured the fixture's firm attachment to the ceiling. The chandelier and reflector were each connected to their own series of weights by "wrist-width" steel cables. While they were supposed to be kept insulated from the cables, electrical wires ran alongside to a power source. Forensic specialists at the time speculated that, based on the distinctive break in the cables, one of these wires came in contact with the two cables, short-circuited the system, and generated enough heat to melt through the steel of the cables. Because each object was hung by a number of counterweights, however, the bronze reflector to which the faulty cables were connected did not fall (it was not, contrary to popular belief, the chandelier that fell), rather the weights themselves came loose to the surprise of the opera's patrons. In addition, each counterweight was comprised of eighteen disks. As the weights fell the pins holding the disks together sheared, and the disks fell over a more widespread seating area. This increased the number of injuries, but, with the exception of a single casualty, it diminished the mass and severity of a blow from any given projectile. The disks fell through the ornate ceiling, through the unoccupied fifth tier, and came to rest on the fourth tier's guests. Mme. Chomette, one of the unfortunate occupants of the fourth tier, was struck in the head by a girder that had fallen from the fifth tier, trapped until rescue workers were notified she was missing by her daughter, and was pronounced dead when workers found her.

116 years ago on May 20, 1896, Paris newspapers were filled with news of an incident that left the French arts culture reeling. At exactly 8:57 p.m., during a performance of the opera Helle', two 360 kg (about 792 lbs. each) counterweights fell from the chandelier above the audience, which killed one spectator and injured many others.

An original advertisement for the premier of Helle in 1896

The Cantilene from Helle, sung by Rose Caron

The chandelier and bronze reflector behind the chandelier were supported by a system of counterweights that insured the fixture's firm attachment to the ceiling. The chandelier and reflector were each connected to their own series of weights by "wrist-width" steel cables. While they were supposed to be kept insulated from the cables, electrical wires ran alongside to a power source. Forensic specialists at the time speculated that, based on the distinctive break in the cables, one of these wires came in contact with the two cables, short-circuited the system, and generated enough heat to melt through the steel of the cables. Because each object was hung by a number of counterweights, however, the bronze reflector to which the faulty cables were connected did not fall (it was not, contrary to popular belief, the chandelier that fell), rather the weights themselves came loose to the surprise of the opera's patrons. In addition, each counterweight was comprised of eighteen disks. As the weights fell the pins holding the disks together sheared, and the disks fell over a more widespread seating area. This increased the number of injuries, but, with the exception of a single casualty, it diminished the mass and severity of a blow from any given projectile. The disks fell through the ornate ceiling, through the unoccupied fifth tier, and came to rest on the fourth tier's guests. Mme. Chomette, one of the unfortunate occupants of the fourth tier, was struck in the head by a girder that had fallen from the fifth tier, trapped until rescue workers were notified she was missing by her daughter, and was pronounced dead when workers found her.

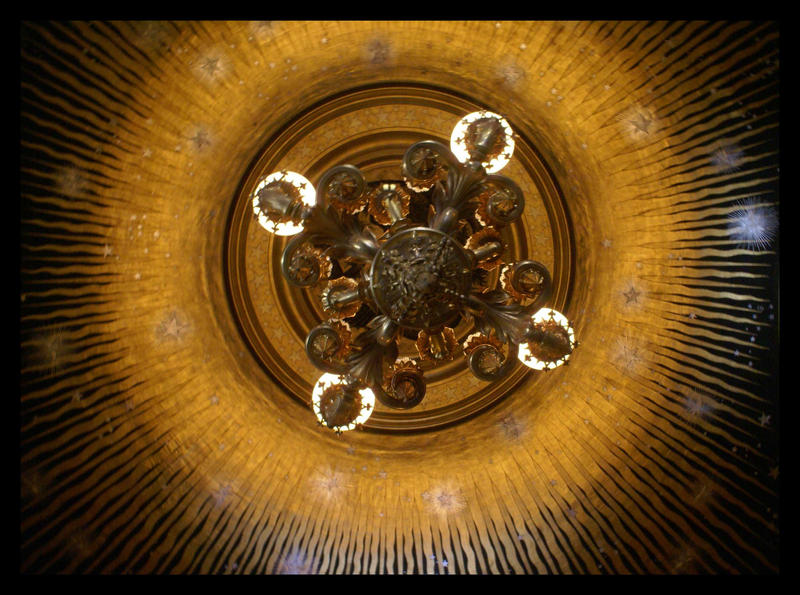

The bronze reflector above the original chandelier in the hall would have resembled this one from the lobby

The chandelier in the Paris Opera House

A keen observer will notice the similarity between the opera house incident in 1896 and Broadway's Phantom of the Opera. In 1909 Gaston Leroux drew inspiration from the counterweight accident in his novel Phantom of the Opera, in which the phantom dislodges the chandelier from an opera house ceiling. The scene is preserved in the Broadway rendition of the novel when a life-sized replica of the Paris chandelier travels over the audience's heads onto stage. Leroux's and Broadway's accounts of the accident are, however, noticeably inaccurate; in 1896 the chandelier itself remained firmly attached to the ceiling, and the projectiles were not structurally integral to its stability. In addition, the chandelier itself weighs in excess of seven tons and would have caused a tremendous amount of damage to all five tiers and their occupants. While enthusiasts of Leroux's story may remain fascinated by his romanticized account of the accident, 1896 opera patrons could count themselves fortunate that his rendition is a fantasy.

Gaston Leroux, author of the novel (not to be confused with the Broadway show) Phantom of the Opera (1909)

The ceiling of the Paris Opera House is a fixture in French cultural controversy for another reason aside from its incompetent electricians. The original artwork on the ceiling, painted by Jules-Eugene Lenepveu, was full of conventional vivacity inspired by Classical and Renaissance Era conventions. Entitled "The Muses and the Hours of the Day and Night," it illustrated Greek mythical characters swirling around the base of the chandelier through dawn, day, dusk, and night playing music. After the counterweight accident in 1896 the ceiling was patched temporarily until the 1950s, when the French Minister of Culture instituted a competition to permanently fix the damage and replace the entire ceiling's artwork around the old chandelier. Marc Chagall, a native Russian Jew (and one of Andy's favorite artists!), won the commission, and was hired despite public outcry. The French people were outraged that a foreigner was allowed to pollute their proud Parisian arts culture, but agitation only grew when the final product was unveiled. Chagall presented an impressionist interpretation of Lenepveu's work. Instead of using Renaissance ideals of human form, Chagall painted caricatures of the Muses in vivid color with an Impressionist flair. Opponents of Chagall's commission considered his work a bastardization of the masterpiece that preceded it, an argument that continues in France to this day; some advocate that Chagall's ceiling be removed to uncover the Lenepveu, which is preserved beneath.

A scaled-down reproduction of Lenepveu's original ceiling. The chandelier and bronze reflector would have hung in the center

Chagall's ceiling as it is today, with chandelier and bronze reflector hanging from the center

The incident of the falling chandelier parts is far more famous than the opera that was being performed that night, ironically titled 'Helle'. The opera itself has faded from most people's memory and the poster for the opera is held in higher artistic regard than the opera. An unfortunately hellish night at the opera.

I love these old flyers and posters. I have several and use them to decorate around my wet bar near my piano. The nostalgia.

ReplyDeleteAmazing what you can find on the internet! Thank you!

ReplyDelete