By Andy Fein, luthier at

Fein Violins

|

| Scroll of a Gasparo da Salo viola, Brescia circa 1609 |

In my role as a violin maker and shop owner, I often hear string players searching for an instrument say, "I don't really care what it looks like, I'm only interested in the sound." To which I usually reply, "If looks didn't count, we could paint them all black and use a square block for the scroll." Obviously, in violin family instruments, looks count. We're all interested in the color and beauty of the varnish, the beauty of the wood, and the artistic details such as the

f holes, the

arching, and the scroll. The scroll is

the top part of the instrument with the completely useless detail of being shaped in expanding concentric circles. Yes, completely useless. A square block would work just as well. But a square block wouldn't look nearly as nice. Or have so much power in its beauty.

|

| Scroll of an Andrea Amati violin, Cremona circa 1577 |

|

| A bottle with a scroll motif, SouthEastern US circa 1200 |

In fact, to see the most beautiful parts of a violin, viola or cello you have to stop playing and hold the instrument as an art piece. You have to turn the instrument over to see the flamed Maple of the back and you have to hold the instrument close to your face to look at the scroll. Face to face, eye to eye, and nose to nose. For violins and violas, the act of looking at the scroll is the opposite position of playing. (Just another reason cellos rule! Hah, just kidding.....Sort of.)

The scroll motif is a very ancient and universal symbol in art and architecture throughout the world. It's visible in ancient Asian and Middle Eastern art and in Pre-Columbian Native American art.

|

| An ancient abacus with a scroll motif |

But why a scroll on top of stringed instruments? The

earliest violin makers were probably not the innovators of using a scroll on a stringed instrument. There's some evidence that viol family instruments were being made with scrolls as early as the 1400s. But viol makers also used human and animal heads at least as often. It's in the violin family that we see the scroll become the standard piece of headstock. In Italian, the scroll is called "la testa", the head.

So how do we get to a scroll? Especially the type of scroll that incorporates a flowing reverse curve into the pegbox.

|

| Side view, the scroll of the 'Messiah' Stradivarius violin |

|

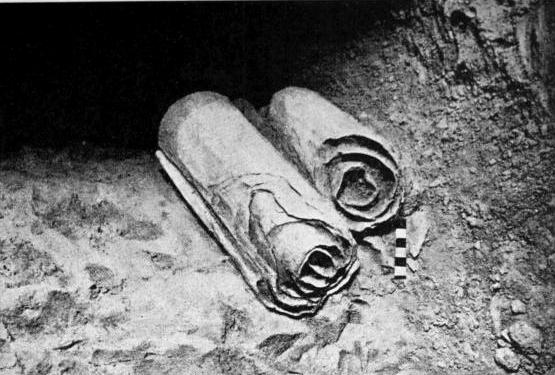

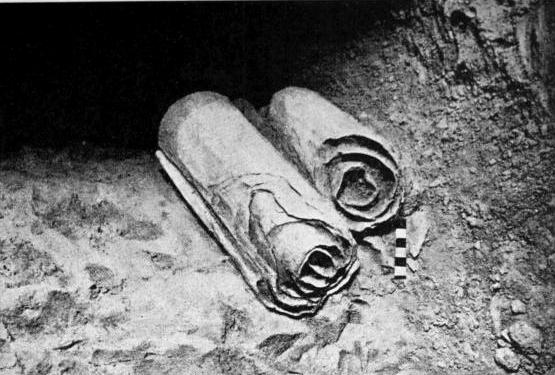

| Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls before they were unraveled |

|

| Roman papyrus scroll preserved by volcanic ash, Southern Italy circa 79 CE |

|

| The perfect violin scroll? The 'Messiah' Stradivarius violin, Cremona, circa 1716 |

|

One side of a Torah scroll

|

First, some ancient history on writing and record keeping. Books were not invented as a form to keep

written documents in until the first century CE (Common Era). Before then, documents were rolled up and stored as a single or double cylinder. Being the moderately good Torah scholar that I am, when I first learned the top of a violin was called a scroll, I compared it to a Torah Scroll (containing the Five Books of Moses) or the Book of Esther Scroll (The Megillah). How does a violin scroll relate to an ancient written scroll? If you look at the ancient scrolls from the top to the bottom of the rolled up part you can see that the violin scroll is an artistic carving of a written scroll. Make your own scroll and see. Take a large piece of paper, roll it up, then let it unfurl a bit. View it from the top or the bottom. Voila! A violin scroll shape.

|

| Megillah |

This type of scroll motif is called a Vitruvian Scroll, named after a Roman architectural historian from the first century BCE (Before the Common Era) Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, one of the first people to describe its use in architecture.

|

| Vitruvian scrolls |

|

| Scroll, Andrea Guarnerius viola, the 'Primrose' , Cremona circa 1697 |

|

| Scroll, Stradivarius violin, Cremona, circa 1722 |

|

| Scroll, Antonio Gragnani violin, Livorno circa 1788 |

You can also get a similar scroll design

by drawing the areas of the Fibonacci Sequence. C'mon, get your geek on! Fibonacci Sequence- the series of numbers you get by adding up the two numbers before it. 0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34..... Once you know and can visualize the Fibonacci Sequence you'll start seeing it all around you. In nature, in art and design, and in violin scrolls. Was the Fibonacci Sequence known to early violin makers? Probably. Fibonacci lived from circa 1170 to circa 1250 in Pisa, Italy, and was a well known Italian mathematician.

|

| A Fibonacci Spiral |

|

| Scroll, 'King Henry IV' Amati violin, Cremona circa 1595 |

Whether the early violin makers took their cues from Vitruvian Scrolls or Fibonacci Scrolls, or both, the scroll motif has been used to symbolize heavenly power, harmony, and unending possibilities (such as the waves of the ocean). Hmm, I'll put that on top of my violin any time! Did the early violin makers think along those lines? No one knows. But nothing happens on a violin without a reason. Surely the scroll had some or all of this symbolism to the first violin makers.

|

| Scroll, Andrea Amati violin, Cremona circa 1577 |

|

| Scroll, G.P. Maggini violin, Brescia circa 1632 |

By the way, carving a violin scroll is not an easy thing! The violin maker has to be constantly comparing and balancing all four sides - front, back, and both sides. Each side and feature should look the same from all the angles. Unless you're Guarnerius del Gesu. Then you can make a flop eared scroll look cool.

|

| The scroll of Paganini's 'Il Canone' violin by Guarnerius del Gesu, Cremona circa 1742 |

|

| A set of scroll gouges, used for carving a violin,viola or cello scroll |

So now that you know so much about scrolls, look at the scroll on your instrument. Are the ears the same size and do they align? Do the curves flow into each other? Are the curves more circular or oval? Do you think it's beautiful? Do you like how the curves of the scroll flow into the curve of the pegbox? What do you think- Is the beauty of the scroll important? Or could a square block serve the same function?

|

Scroll, Andrea Amati violin, Cremona circa 1570

|

|

| Violin Scroll, Peter Guarnerius, circa 1732 |

.jpg) |

| Three beautiful violin scrolls. Gaetano Gadda on the right; Giuseppe Nupieri, center; Haim Rappaport on the left. |

|

| J.B.Vuillaume cello, 1841 |

|

Scrolls- Cerin, 1792, center; Storioni, 1793, right; Gragnani, 1788, left; Mantegazza, 1793, back

J.B. Vuillaume cello, 1841 |

|

| Scroll, J.E. Zust violin, Zurich, 1922 |

|

| Scroll, the 'Harrison' Stradivarius, Cremona circa 1693 |

|

| Scroll, the 'Ole Bull' Guarnerius del Gesu, Cremona, 1744 |

Are you a violinist or interested in becoming one? Tale a look at our

Fine Violins!

.jpg)

I would imagine a square block could functionally serve but wouldn't the balance of the instrument also be changed?

ReplyDeleteYou're probably right, James. I'm speaking metaphorically about substituting a square block for the scroll. I don't think anyone would actually use a square block for the scroll.

DeleteI enjoyed the visit down history lane, thanks

ReplyDeleteA beautiful instrument. Which makes a sweet and haunting sound...

ReplyDeleteOK that makes a lot of sense, thanks. But, doesn't the violin need some sort of mass there to help sustain notes or something like that? And, I have watched experienced violinists to something that I still cannot do; turn the tuning pegs with one hand using the scroll as a sort of base for their hand

ReplyDeleteThanks for that. I have a couple of questions, though. Is it possible that the scroll (no matter what shape it is) is there to add mass to the instrument for sustaining notes perhaps. Also, I have seen experienced violinists tune their instruments by holding onto the scroll and turning the pegs (all with one hand) and it seems to me that the scroll seems to fit their hand. Was it perhaps designed with this purpose in mind?

ReplyDeletehas anyone ever measured to see if any sound resonates from the scroll?

ReplyDeleteor maybe it absorbs stray frequencies?

ReplyDeleteThanks for the "primer". Before reading this they all looked the same to me. Now I can feel it. I can see myself actually carving my own scroll.

ReplyDeleteCool! I had no idea! I have always enjoyed running my nose down the back of the scroll and feeling the bumps and polish.

ReplyDeleteThe scroll adds to the final cost. If we did away with it, instruments would be cheaper and take less space while still sounding just as good. But it wouldn't look as good? Big deal! Think about it, it worked just fine for guitars.

ReplyDeleteAfter reading this, I discovered that the 2 sides of the scroll on my violin are slightly different from each other! Oh, no!

ReplyDeleteBut seriously - a very interesting article, thank you. I do agree, the beauty of an instrument is very important, both for player and audience.

harpist over here like what do you mean you can't enjoy your scrolls without turning your instrument the other way round? You can turn it?! Hold it with one hand?! You lucky sods! Meanwhile, over here in the back of the pit, with the gorgeous looking fat angel triangle that no-one can hear!

ReplyDeleteJust joking. Violins are cool.

Isn't it also like the violin is the body of the scroll where the text would be. So when you play it's as if you're opening the scroll

ReplyDeletethe scroll seems to bring life to stringed instruments

ReplyDelete