By Andy Fein, luthier at Fein Violins

Matt Lammers and Amy Tobin

Here in America, we tend to think that we have the monopoly on the idea of 'the great melting pot.' When the rest of the world began their exodus to 'the new world,' New York became an amalgamation of peoples and cultures from everywhere else. We can not, however, lay claim to this phenomenon. In fact, the Piedmont region of Italy was a melting pot of nationalities and cultures long before this happened on our own soil.

The Piedmont region of Italy includes

Turin at its hub, along with Alessandria, Alba, Cuneo, and Torre Pellice forming part of its perimeter. Geographically, it is part of Italy. Its proximity to France, Switzerland, and to some extent Austria, made it susceptible to outside forces.

This region was originally ruled by the Duke of Savoy, who would later become the King of Sardinia. The reign of the Savoy dynasty had begun in 1562 and, during its time, had created a society that was home to some of the greatest musicians and orchestras there were. There were two court orchestras: the Capella Regia (the Royal Chapel Orchestra) and the Capella del Duomo (the Cathedral Chapel Orchestra). The Savoy sovereigns went in search of the finest and best musicians, brought them to their orchestras, and paid them handsomely. This concentration of great musicians contributed to a thriving group of theaters, around which a tight community of artists and patrons was established. There was also a rich tradition of violin pedagogy, with a school headed by Giovanni Battista Somis, a student of Corelli. In fact, Somis would later be the connecting link between Turin and Paris, having tought Jean-Marie Leclair, who would go on to found the French violin school, bringing the Italian musical sensibility to France. (Interesting side note: After moving to Paris post break-up from his second wife, he died from a stab in the back; this murder was mysteriously unsolved.)

Before parts of Italy were seized by French revolutionaries in the early 1790s two schools of violin making nourished the needs of musicians that performed with these reputable orchestras and theaters. The first and largest of the two Piedmontese schools was a hybridized system of violin making pieced together from French techniques and an awareness of old Cremonese forms (although they were never compelled to replicate them pre-1790). The French style of construction used the external form, which involved cutting the back plate and fitting the ribs to it, followed by the top plate. This method produced violins that were consistently similar to the pattern in a time efficient manner. The second, consisting of a much smaller group of violin makers, is best represented by Giovanni Battista Guadagnini (or J.B. Guadagnini). Having moved to Turin from Parma in 1771 (late in life), his style developed independent of French influence. Guadagnini was well versed in the Lombard tradition of violin making from Cremona, but, having taught himself, took artistic liberties aside from basic construction. As old Cremonese conventions dictated, Guadagnini used an internal form, where the ribs were constructed around a pattern and the back and top plates fitted to them. This method allowed Guadagnini to develop the creativity, freedom, and favorable inconsistency he is known for.

Both the Piedmont-French and Lombard-Guadagnini schools underwent significant transformations as 1790 came and went. G.B. Guadagnini died in 1786, leaving the shop to his sons Carlo and Gaetano. The two sons learned what they could from their father in the few years before his death and carried on the Lombard tradition of making in Turin. The Piedmont-French school, which acts as a convenient historical indicator of French culture, became reflective of French Revolutionary and Napoleanic ideals. French revolutionaries considered their victory a triumph of reason and themselves successors of the ancient Greeks and Romans. This heightened level of historical responsibility encouraged French violin makers (who flooded the Piedmont Region once it was annexed to France) to pay homage to the roots of violin making: the old luthiers of Cremona. They began using the patterns and replicating the violins of Stradivarius and his contemporaries, but did so using the external form of construction. This completed the hybridization of French and old Italian violin making and became the trademark style of Piedmontese violin making instead of the Lombard-Guadagnini method.

One of the most significant violin shops making in this new Piedmontese style opened its doors in the 1790s. Nicolas Lete, a Frenchman who had already established shops in Paris and Bruxelles, married Christine Pillement, the daughter of a prominent Mirecourt violin maker and the mayor of that very city, and founded his third violin making operation in Turin under their joint name: Lete-Pillement. The shop produced its instruments from Stradivarius patterns in a high volume, as the use of external forms allowed them to do so.

The next chapter in Piedmontese violin making began as French hostilities came to an end in 1814, and the Guadagnini and Lete-Pillement shops (still the two most prominent shops in Turin and representative of the two styles of violin making that went on there) underwent another period of change. Carlo and Gaetano Guadagnini died suddenly in 1816 and 1817 respectively, leaving the shop to Carlo's son Gaetano II. While the Guadagnini establishment was enduring times of hardship as young Gaetano II occupied himself with learning the craft from his grandfather's notes, Nicolas Lete took the opportunity to move permanently from Mirecourt to Turin with his family. Doing so gave him the freedom to invest time in apprentices. These were self-taught, amateur violin makers living on other professions (often of rural upbringing) in whom he saw undeveloped talent and promise. A peasant laborer Giovanni Francesco Pressenda was one such promising amateur, and Lete employed him in 1817. He was trained masterfully in the Piedmont style for two years until Lete's death in 1819. While the Lete-Pillement shop would close in 1827 after eight years of ineffective management, it cemented its legacy as the originator of the Piedmont style by producing the first true legend of the school: Pressenda, who opened his own shop in 1820.

As the Pressenda shop built upon its reputation and fine violin making, the Guadagnini shop (owned by Gaetano II) found itself in something of a holding pattern. Gaetano II recognized that his talent was not in violin making, but in guitar making and instrument dealing. As such, until his death in 1852, the shop's violin output dropped significantly. This strategic move kept the shop in business, whereas the violins he made (of a somewhat lower quality than his Grandfather's, Father's, and Uncle's instruments) would have likely closed the shop's doors had they been his primary output. During this time, however, he began hiring apprentices as Pressenda did, a practice that his son Antonio upheld when he inherited the shop in 1852.

While the Guadagnini shop was occupied with producing guitars from when Gaetano II took over until his death in 1852, Pressenda employed his two most notable apprentices: Giuseppe Rocca and Teobaldo Rinaldi. Rocca came to work with Pressenda in 1837 after the shop he tried to establish was met with bankruptcy after a year. Whether it was out of admission from Pressenda that Rocca was skilled enough in his ways to continue without guidance or out of Rocca's bitter resentment that his shop failed, Rocca did not adopt many Piedmont style techniques. He used an internal form, based his instruments on different models than the rest of Pressenda's instruments, and his finishing methods were unlike any other work to come out of the shop. Quite possibly due to the resulting tensions between the two, Rocca left Pressenda in 1851 to try once more to open his own shop, this time in Genoa. In 1857 he moved back to Turin in the hopes of finding less competition with the death of Pressenda, but was disappointed to find a thriving Guadagnini shop just five years after the death of the modest guitar maker Gaetano II. In addition, the Pressenda shop was kept alive by his son Joannes Franciscus Pressenda, who was an extremely skilled maker. Joannes, however, was a poor businessman, and the Pressenda shop joined its founder in death a relatively short time later.

Matt Lammers and Amy Tobin

Here in America, we tend to think that we have the monopoly on the idea of 'the great melting pot.' When the rest of the world began their exodus to 'the new world,' New York became an amalgamation of peoples and cultures from everywhere else. We can not, however, lay claim to this phenomenon. In fact, the Piedmont region of Italy was a melting pot of nationalities and cultures long before this happened on our own soil.

The Piedmont region of Italy includes

Turin at its hub, along with Alessandria, Alba, Cuneo, and Torre Pellice forming part of its perimeter. Geographically, it is part of Italy. Its proximity to France, Switzerland, and to some extent Austria, made it susceptible to outside forces.

This region was originally ruled by the Duke of Savoy, who would later become the King of Sardinia. The reign of the Savoy dynasty had begun in 1562 and, during its time, had created a society that was home to some of the greatest musicians and orchestras there were. There were two court orchestras: the Capella Regia (the Royal Chapel Orchestra) and the Capella del Duomo (the Cathedral Chapel Orchestra). The Savoy sovereigns went in search of the finest and best musicians, brought them to their orchestras, and paid them handsomely. This concentration of great musicians contributed to a thriving group of theaters, around which a tight community of artists and patrons was established. There was also a rich tradition of violin pedagogy, with a school headed by Giovanni Battista Somis, a student of Corelli. In fact, Somis would later be the connecting link between Turin and Paris, having tought Jean-Marie Leclair, who would go on to found the French violin school, bringing the Italian musical sensibility to France. (Interesting side note: After moving to Paris post break-up from his second wife, he died from a stab in the back; this murder was mysteriously unsolved.)

| |

| Giovanni Battista Somis |

Before parts of Italy were seized by French revolutionaries in the early 1790s two schools of violin making nourished the needs of musicians that performed with these reputable orchestras and theaters. The first and largest of the two Piedmontese schools was a hybridized system of violin making pieced together from French techniques and an awareness of old Cremonese forms (although they were never compelled to replicate them pre-1790). The French style of construction used the external form, which involved cutting the back plate and fitting the ribs to it, followed by the top plate. This method produced violins that were consistently similar to the pattern in a time efficient manner. The second, consisting of a much smaller group of violin makers, is best represented by Giovanni Battista Guadagnini (or J.B. Guadagnini). Having moved to Turin from Parma in 1771 (late in life), his style developed independent of French influence. Guadagnini was well versed in the Lombard tradition of violin making from Cremona, but, having taught himself, took artistic liberties aside from basic construction. As old Cremonese conventions dictated, Guadagnini used an internal form, where the ribs were constructed around a pattern and the back and top plates fitted to them. This method allowed Guadagnini to develop the creativity, freedom, and favorable inconsistency he is known for.

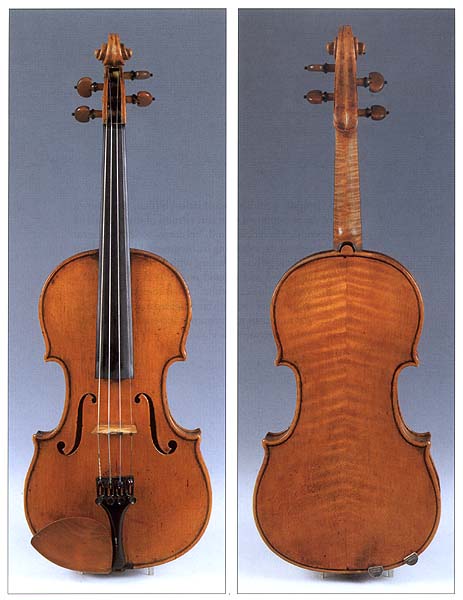

A 1752 G.B. Guadagnini violin, made during his Parma years before Turin

A 1784 late G.B. Guadagnini violin, made in Turin

In 2011 Tarisio Auctions sold the legendary conductor-violinist Lorin Maazel's 1783 G.B. Guadagnini for $1,080,000

Both the Piedmont-French and Lombard-Guadagnini schools underwent significant transformations as 1790 came and went. G.B. Guadagnini died in 1786, leaving the shop to his sons Carlo and Gaetano. The two sons learned what they could from their father in the few years before his death and carried on the Lombard tradition of making in Turin. The Piedmont-French school, which acts as a convenient historical indicator of French culture, became reflective of French Revolutionary and Napoleanic ideals. French revolutionaries considered their victory a triumph of reason and themselves successors of the ancient Greeks and Romans. This heightened level of historical responsibility encouraged French violin makers (who flooded the Piedmont Region once it was annexed to France) to pay homage to the roots of violin making: the old luthiers of Cremona. They began using the patterns and replicating the violins of Stradivarius and his contemporaries, but did so using the external form of construction. This completed the hybridization of French and old Italian violin making and became the trademark style of Piedmontese violin making instead of the Lombard-Guadagnini method.

While the French Revolution inspired recognition of old Cremonese luthiers, its effects on their legacies were not strictly beneficial. The "King" Amati cello, made in 1538, is the oldest known bass instrument in the violin family and was made as part of a set commissioned by the French royal family. This set was broken apart and many of Amati's instruments were destroyed during the Revolution.

One of the most significant violin shops making in this new Piedmontese style opened its doors in the 1790s. Nicolas Lete, a Frenchman who had already established shops in Paris and Bruxelles, married Christine Pillement, the daughter of a prominent Mirecourt violin maker and the mayor of that very city, and founded his third violin making operation in Turin under their joint name: Lete-Pillement. The shop produced its instruments from Stradivarius patterns in a high volume, as the use of external forms allowed them to do so.

A violin made in 1840 by one of Lete-Pillement's finest employees: Giovanni Francesco Pressenda

The next chapter in Piedmontese violin making began as French hostilities came to an end in 1814, and the Guadagnini and Lete-Pillement shops (still the two most prominent shops in Turin and representative of the two styles of violin making that went on there) underwent another period of change. Carlo and Gaetano Guadagnini died suddenly in 1816 and 1817 respectively, leaving the shop to Carlo's son Gaetano II. While the Guadagnini establishment was enduring times of hardship as young Gaetano II occupied himself with learning the craft from his grandfather's notes, Nicolas Lete took the opportunity to move permanently from Mirecourt to Turin with his family. Doing so gave him the freedom to invest time in apprentices. These were self-taught, amateur violin makers living on other professions (often of rural upbringing) in whom he saw undeveloped talent and promise. A peasant laborer Giovanni Francesco Pressenda was one such promising amateur, and Lete employed him in 1817. He was trained masterfully in the Piedmont style for two years until Lete's death in 1819. While the Lete-Pillement shop would close in 1827 after eight years of ineffective management, it cemented its legacy as the originator of the Piedmont style by producing the first true legend of the school: Pressenda, who opened his own shop in 1820.

An 1829 Pressenda made soon after the collapse of Lete-Pillement

The Pressenda shop, in the seven years between its founding and the closing of Lete-Pillement, laid its foundation in Turin. Throughout the gradual decline of Lete-Pillement the Pressenda shop earned prestige through competition and growing revenues as business was redirected his way by Lete's widow. This placed Pressenda in the ideal position to gradually and gracefully take over the helm of Piedmont style violin making after his late boss. Once his reputation was solidified, Pressenda began hiring apprentices (among them was his former Lete-Pillement colleague Francois Calot) and other luthiers (one of which was the masterful Frenchman Pierre Pacherel).

An 1836 Pacherel violin, made before his time in the Pressenda shop

As the Pressenda shop built upon its reputation and fine violin making, the Guadagnini shop (owned by Gaetano II) found itself in something of a holding pattern. Gaetano II recognized that his talent was not in violin making, but in guitar making and instrument dealing. As such, until his death in 1852, the shop's violin output dropped significantly. This strategic move kept the shop in business, whereas the violins he made (of a somewhat lower quality than his Grandfather's, Father's, and Uncle's instruments) would have likely closed the shop's doors had they been his primary output. During this time, however, he began hiring apprentices as Pressenda did, a practice that his son Antonio upheld when he inherited the shop in 1852.

An 1821 Gaetano II Guadagnini guitar, made soon after the deaths of his Father and Uncle in 1817

Antonio's violin making skill was, like his father, not at the level of his predecessors (though still remarkable). Instead Antonio learned to recognize superior violin makers with enormous potential, took advantage of his father's apprenticeship precedent, and hired a handful of makers that would revitalize the prestige that was guarded and conserved by Gaetano II. Among these master "apprentices" were Enrico Marchetti and Maurice Mermillot, who, by virtue of employment by the Guadagninis, continued to make violins in the old Italian style with Lombard techniques.

An 1895 Marchetti violin, made after his time in the Guadagnini shop

While the Guadagnini shop was occupied with producing guitars from when Gaetano II took over until his death in 1852, Pressenda employed his two most notable apprentices: Giuseppe Rocca and Teobaldo Rinaldi. Rocca came to work with Pressenda in 1837 after the shop he tried to establish was met with bankruptcy after a year. Whether it was out of admission from Pressenda that Rocca was skilled enough in his ways to continue without guidance or out of Rocca's bitter resentment that his shop failed, Rocca did not adopt many Piedmont style techniques. He used an internal form, based his instruments on different models than the rest of Pressenda's instruments, and his finishing methods were unlike any other work to come out of the shop. Quite possibly due to the resulting tensions between the two, Rocca left Pressenda in 1851 to try once more to open his own shop, this time in Genoa. In 1857 he moved back to Turin in the hopes of finding less competition with the death of Pressenda, but was disappointed to find a thriving Guadagnini shop just five years after the death of the modest guitar maker Gaetano II. In addition, the Pressenda shop was kept alive by his son Joannes Franciscus Pressenda, who was an extremely skilled maker. Joannes, however, was a poor businessman, and the Pressenda shop joined its founder in death a relatively short time later.

An 1843 Rocca violin, made during his time at the Pressenda shop

An 1849 Joannes Pressenda violin, made before he inherited Giovanni's shop

While Rocca's legacy as a violin maker and student of the Piedmont style was relatively short lived, Rinaldi and his descendants carried on the Pressenda-Lete-Pillement legacy. After Pressenda's death an instrument dealership in the Rinaldi name was registered in 1859. Rinaldi, like Rocca, was not long after forced out of business by Antonio Guadagnini, and the Rinaldi name was not seen again until the early 1870s. This time, however, it was his son-in-law Benedetto Gioffredo who opened a shop. Benedetto took advantage of Rinaldi's reputation in the former Pressenda shop by adopting his wife's maiden name, gleaned what he could from his aged father-in-law, and established his own reputation as a masterful repairer. The new Rinaldi shop was far more successful than Teobaldo's attempt and rivaled Guadagnini's. Benedetto possessed many of the same skills as Antonio; he produced very few of his own instruments (which were, however, exemplary), focused on dealing and repairs, and hired a handful of talented apprentices that stayed with him through the 1880s. These apprentices, who included the noteworthy luthier Giuseppe Oddone, continued to nurture the Piedmont style and techniques of violin making.

In short, Turin, being the cultural, industrial, and political capital of Piedmont Italy was home to two distinctive schools of violin making that developed side by side. The Lombard school has existed since the genesis of violin making, and the Piedmont school began its history as far back as French-Italian commerce has flourished. The first turned away techniques pioneered by the masters of Mirecourt, and the second embraced them creating a French-Italian hybrid style. Giovanni Guadagnini, his ancestors, and their employees were the primary caretakers of Lombard school making, while Nicolas Lete and the lineage of those he trained upheld the legitimacy of the Piedmont style. It's remarkable to consider that, despite more than a century of competition within the small proximity of Turin's walls, both schools flourished and produced some of the highest quality instruments the world has seen.

A 1747 Giovanni Guadagnini violin, made before he settled in Turin

A 1757 Giovanni Guadagnini violin, made before he settled in Turin

A 1760 Giovanni Guadagnini violin, made before he settled in Turin

A 1776 Giovanni Guadagnini violin, made five years after he settled in Turin

Are you a violinist or interested in becoming one? Take a look at our Fine Violins!

Dear Andy,

ReplyDeleteI loved reading this article. You are so knowledgeable, ... of course that means drawing from a wide variety of sources. So its the interpretation, a sense of what is important, reliable, and meaningful in terms of the larger story created that I find so interesting in your writing.

Its been a while since we connected ...I miss our conversations about these things. I am working at the moment on preparations for exhibiting the Messiah Stradivari in a return visit to the city of its birth. Looking for some close replicas of the Messiah made by G Rocca so as to help viewer better appreciate the importance of this Stradivari.

Let's keep in touch, OK?

Gregg Alf

4175 Cannaregio

Venezia, VE

ITALIA 30121

+39 328 155 5548