By Andy Fein, Luthier, Fein Violins, Ltd.

If you've ever seen someone struggling down the street or up the stairs with a cello, your first thought might be "Wow! Those are big instruments!" Well, in the very long history of cellos, many of them used to be even bigger.

The standard body length of a modern cellos is about 750mm (29 1/2"). Before 1700, some monster cellos, even those made by great makers, were 760mm to 800mm (30" to 31.5"). These big cello were also proportionately wider in width. Think about that the next time you need to reach around your cello's upper bouts to play in upper positions!

Pablo Ferrandez plays on the 'Aylesford' Stradivarius cello

If you've read some of our earlier blogs, you'll know that the note we know as A (440 Hz) used to be lower in pitch. And the pitch varied all over Europe. Strangely, it seems the further south that you went, particularly in Italy, the lower the pitch. In the 1600s, A was often about 390Hz in Rome.

Cellist Robert Cohen plays on a somewhat large cello made by David Tecchler in Rome, circa 1723

What did this mean for cellos? It meant that the low C string was very, very low. And the low pitch required a large amount of air inside the instrument to power the lower strings. The air inside a cello has a fundamental frequency, a note where it vibrates best. Sing a scale with your voice directed into the f hole. My guess is you'll feel the cello vibrate with your singing right about the note G. That's the fundamental frequency of the air inside the cello. A bigger cello means more air inside the cello and a lower fundamental frequency. So lower tuning would necessitate a bigger cello.

For a myriad of reasons, the note A kept rising. Eventually the big cellos were out of range of the sympathetic vibrations they needed to play well. Unfortunately, that meant that most cellos by great makers were eventually "cut down", a process that entails reshaping the top, back, and ribs of the cello to a smaller body length.

One of the oldest cellos still in existence, the 'King' Amati shows sign of being cut down. Look at the woman in the center of the cello. She's missing her waist!

One of the few Stradivarius cellos that has not been cut down is the Castelbarco cello. It retains its body length of about 792mm (31 1/4"). Made in 1699, it is in the collection of the U.S. Library of Congress and can sometimes be seen and heard in the Performing Arts Reading Room.

Other makers who made larger model cellos include: Guarneri, Tecchler, Goffriller, and Testore.

Here at Fein Violins we have pretty standard measurements for cellos. You can view our cellos here --> Fein Cellos

If you've ever seen someone struggling down the street or up the stairs with a cello, your first thought might be "Wow! Those are big instruments!" Well, in the very long history of cellos, many of them used to be even bigger.

|

| The 'Lord Aylesford' Stradivarius cello. A BIG cello |

If you've read some of our earlier blogs, you'll know that the note we know as A (440 Hz) used to be lower in pitch. And the pitch varied all over Europe. Strangely, it seems the further south that you went, particularly in Italy, the lower the pitch. In the 1600s, A was often about 390Hz in Rome.

Cellist Robert Cohen plays on a somewhat large cello made by David Tecchler in Rome, circa 1723

Robert Cohen playing the Beethoven Sonata for Cello, No.2, in G Minor

What did this mean for cellos? It meant that the low C string was very, very low. And the low pitch required a large amount of air inside the instrument to power the lower strings. The air inside a cello has a fundamental frequency, a note where it vibrates best. Sing a scale with your voice directed into the f hole. My guess is you'll feel the cello vibrate with your singing right about the note G. That's the fundamental frequency of the air inside the cello. A bigger cello means more air inside the cello and a lower fundamental frequency. So lower tuning would necessitate a bigger cello.

For a myriad of reasons, the note A kept rising. Eventually the big cellos were out of range of the sympathetic vibrations they needed to play well. Unfortunately, that meant that most cellos by great makers were eventually "cut down", a process that entails reshaping the top, back, and ribs of the cello to a smaller body length.

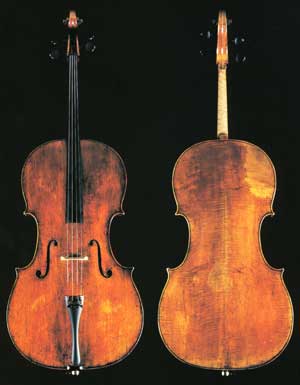

One of the oldest cellos still in existence, the 'King' Amati shows sign of being cut down. Look at the woman in the center of the cello. She's missing her waist!

|

| The 'Castelbarco' Stradivarius cello of 1699 |

Other makers who made larger model cellos include: Guarneri, Tecchler, Goffriller, and Testore.

Here at Fein Violins we have pretty standard measurements for cellos. You can view our cellos here --> Fein Cellos

nice

ReplyDeleteHow do they change the purfling to match the smaller radii of the bouts.

ReplyDeleteThe Hutchins Baritone Violin is basically a modern revival of those big 15th & 16th century Cellos & rather than reduce the body length, she actually cut down the height of the ribs.

ReplyDelete