and Ivana Truong

Where did the violin family come from?

John Huber, a PhD musicologist with a special interest in the physical developments of violin family instruments, has written a fascinating and in depth book tracing the developments that eventually led to the violin. The developments go far back in history. Way back. Maybe as far back as 30,000 years.

Dr. Huber's book BC Before Cremona gives the reader an in depth and fascinating look into the developments that led to the violin. With great pictures, intense research, and keen observation, Dr. Huber takes the reader on a fascinating journey that brings string players and readers through a tremendous amount of human history. Reading "BC Before Cremona" it seems like making music and bowing strings is an integral part of human development.

The first 'guiding arrow' to stringed instruments was the hunting bow, invented as long as 30,000 years ago. By using bows, early hunters were seeing strings as they would be used on an instrument. There are even cave paintings from 13,000 BCE believed to be depicting a hunting bow itself being used as a single stringed instrument. As the hunting bow spread, more people were able to see this use of strings, and 2 basic instrument types developed: the lute and the harp. The harp creates more notes by adding more strings, while the lute creates more notes by altering the length of vibrating string with the finger, like a violin. We're using 'lute' in this sense not too mean the somewhat modern instrument that is a predecessor of the guitar, but in the organology (the study and classification of musical instruments) sense of a rudimentary instrument with one or a few vibrating strings.

|

| Cave painting of a hunting bow used as an instrument image from www.harphistory.info |

|

| A South African playing the musical bow. "With a little stick he plays the string, his mouth being the soundboard" image from www.harphistory.info |

|

| "A North African rebec with a skin top" Used by permission of the author and publisher of BC, Before Cremona, All rights reserved |

|

| "a characteristic modern dotar constructed from prepared parts" Used by permission of the author and publisher of BC, Before Cremona, All rights reserved |

|

| Depiction of a harp in an Egyptian tomb from as early as 3,000BC image from International Harp Museum |

One lute-type instrument is the spike fiddle. A spike fiddle is made with a wooden rod and a body, sometimes a gourd or wooden box. It usually has 2-4 strings, which are adjusted with tuning pegs. Though there are plucked varieties, like the kabuli rebab, most are bowed, a huge development. The first instrument bows (basically a bent stick with horsehair attached) were developed by nomads who lived in the north-east Asian steppes. After its development and diffusion, the bow was applied to both harps and lutes. Since the lute has fewer strings, the bow was more practical and remained part of some lute instruments.

| |

A Chinese stick fiddle, the Erhu

|

|

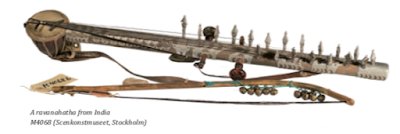

| "A ravanahatha from India" Used by permission of the author and publisher of BC, Before Cremona, All rights reserved |

|

| A bowed harp called the Psaltery image from a youtube video |

|

| A type of spike fiddle that a customer brought back from Burkina Faso. The instrument has several names, including Goje (Huasa), Gonjey (Dagomba, Gurunsi), and Riti (Fula, Serer). |

After the bow spread to Europe with the help of the Silk Road, the medieval vielle, or fiddle, rose to prominence. Unlike spike fiddles, which are played upright, the vielle is played on the shoulder. But the vielle is still far from what we would today call a violin. At this point, most instruments were still made by the musicians themselves. Since most instruments were spike fiddles or carved out of whole blocks of wood, it was fairly easy for an amateur to make a functional, though maybe not beautiful, instrument. As long as musicians could easily make their own instruments, the market wouldn't support skilled workshops.

|

| A Painting by Hans Memling where an angel plays the Vielle Used by permission of the author and publisher of BC, Before Cremona, All rights reserved |

|

| A Tenor Vielle made in 1959 image from Museum of Fine Arts Boston |

One of the most important factors that led to the growth of workshops was more complicated instrument construction. In 822CE, Ziryab, an Iraqi poet, composer, and teacher, constructed an Ud, a lute-type instrument, using techniques from Baghdad. The new technique consisted of "making thin strips of wood, cutting them to shape, bending them to fit together and accurately assembling the seg- ments into a strong, light “eggshell” form attached to a neck to which a thin wooden top was added". This technique is the basis of how violins are constructed today and it requires far more skill than a single-block construction. Musicians couldn't easily make this style of instrument, and this contributed to the need for luthiers. Imagine asking a violinist, violist, or cellist today to make their own instrument; it would be a disaster. Still, workshops only emerged when cities grew, the technique was popularized, and a sufficiently rich and interested group of aristocracy funded development.

| |

An Islamic Ud made with prepared parts rather than single-block construction

|

Once workshops were established and funded, more experimentation and refinement was possible. Early string instruments could be both plucked and bowed, so they had lower bridges and a guitar-like form instead of the more specialized form we have today. Generally, there was a lot of room for improvement. In the 1400's-1500's Ferraran makers perfected the higher, arched bridge, inserted ribs, and arched the soundboard. In the 1480's, the Kingdom of Aragon had Vihuela de arcos and fiddles with defined corners. By 1530-1550 the instrument had an arched body, a bass-bar, and a soundpost. After centuries of evolution, the instrument could finally be called a 'violin'.

|

| image of string instruments in the musical textbook 'Musica Instrumentalis Duedsch' (1528-1545) |

|

| 1500 painting of a Lira da Braccio with corners |

|

| "A modern copy of a Renaissance Italian Lira del Bracio" Used by permission of the author and publisher of BC, Before Cremona, All rights reserved |

Most of this post uses information from the book B.C. Before Cremona by John Huber, which we were given an advanced copy of. Though it, like most academic reads, is dense at times, it presents interesting ideas. Obviously, the book goes into much more detail than this blog post and it incorporates history into the development of the violin. The string instrument community has a certain infatuation with Cremona and all its great luthiers, as does anyone with a love for fine instruments. But in terms of the musical research and articles available, it can be all consuming. It's refreshing to hear about the history and development leading up to Cremona. If you enjoyed learning about the violin 'Before Cremona', consider getting a copy of BC Before Cremona.

For further reading, Edward Heron-Allen's book Violin Making As It Was and Is provides some insights into the development of the violin family.

You can see many examples of early bowed instruments from many parts of the world, and many very early violin family instruments, at the National Music Museum. But do it soon! They're closing in early October of 2018 for an extended period of time for reconstruction and expansion.

Addendum- October 21, 2018- Recently, archaeologists in Italy think they may have found an ancient instrument that might have been a stick fiddle. Follow the link to see and hear their proposal,

No comments:

Post a Comment