By Andy Fein, Luthier at Fein Violins

and Kevin Berdine

The beloved cello that we know today as a relatively standardized instrument was not always so. Cellos can be traced back to Amati (1581-1632), Gaspar da Salo (1549-1609), and Paolo Maggini (1581-1632). Although still quite recognizable to a modern eye and ear, these proto-cellos were quite different in a number of ways; string material and tuning, neck length and angle, body dimensions, bridge dimensions, arching, bass-bar placement and dimensions, bow design, soundpost dimensions, and even the way in which players held the instrument and bow. For a brief primer, check out Emily Davidson's emilyplayscello Instagram reel.

The driving forces that propelled design changes, not surprisingly, were playability and sound projection. Simultaneously, while composers were demanding more virtuosity from cellists, performing venues were becoming larger as they shifted from churches to courts to concert halls. This compelled instrument makers to design instruments that allowed for greater agility and a bigger, more-projecting sound.

To achieve a more powerful sound, the high-arched cellos of Amati and early-Stradivari turned into the lower-arched Stradivari "Forma B" inspired instruments that we still play today. In 1710, during Stradivari's golden period, he introduced the first Forma B, the "Gore-Booth" cello to the world. Dimensions: Length of the Back 75.6cm; Widest Width of the Upper Bout 34.2cm; Widest Width of the Lower Bout 43.8cm; Narrowest Width of the Middle Bout 22.9cm.

1710 Stradivari "Gore-Booth" Cello

Today there are roughly 20 "Forma B" cellos in existence. In Stradivari's late-period, he continued on his quest to improve playability by making cellos narrower still.

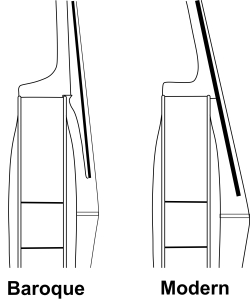

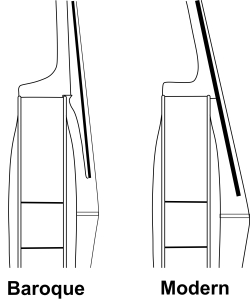

As one can imagine, a lower arch necessitated many other adjustments. Externally, while arching was being lowered neck angles were being increased. This combination required taller bridges to be designed to fit the increased string height. To further add pressure to the top and increase sound-projection of the instrument, metal strings were also added to the mix. In addition to adding tension to the strings by making the bridge taller and switching to metal strings, we also see the tuning raised about whole step. These factors led to important changes that most players do not see. Internally, the soundpost dimensions changed as arching decreased. And the bass bar positioning and dimensions changed to add structural support. Additionally, to add more structural stability, Stradivari made these cellos with more substantial wood thicknesses.

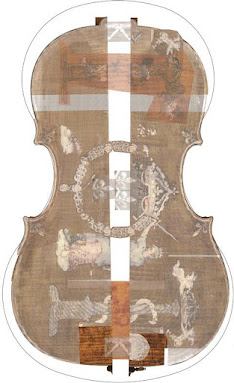

Many great cellos that were made in the Baroque era have since been altered to match modern sensibilities. To achieve a more playable instrument, the overall size was reduced, the neck angle increased, and endpins were added. Additionally, composers began to write music that required more range. Thus neck lengths, too, were increased. Each of the changes allowed a player to navigate around the instrument with greater freedom. Check out this pic, from Matthew Zeller's "Deconstructing the Andrea Amati 'King' Cello," to see how the midsection was removed along the center seam, and the bouts were reduced to cut down the Amati King Cello to modern dimensions.

For those measuring at home, here is a list of the original dimensions versus cut-down dimensions: Length of the Back 78.2cm cut to 75.5cm; Widest Width of the Upper Bout 39.1cm cut to 34.3xm; Widest Width of the Lower Bout 48.9cm cut to 44.2cm; and Narrowest Width of the Middle Bout 27.7cm cut to 23.6cm.

While the instrument itself was undergoing dramatic transformations, so too, was the way in which players held the bow. One will see examples of cellists holding the bow underhand (some bassists still play with "German" bows), overhand above frog (modern hold), and overhand higher up the stick.

Although cellos have remained quite standardized since Stradivari's "Forma B," there continue to be many experiments; carbon fiber instruments and bows, endpin material and angle, tuning pegs material and mechanics, string composition, varnish formulas, interior grounds, artificial aging treatments of wood, neck angles, tailpiece materials and shape, and many other interesting tweaks. What will come next? Nobody knows for sure, but it will surely be playability and sound projection that drive future experiments.

Although playability and sound projection propel most changes, one modern transformation, in honor of comfort and ease, that we have embraced whole-heartedly at Fein Violins, is mechanical pegs. The majority of our instruments leave the shop with these installed. Our clients have absolutely loved the

Wittner Finetune Geared Pegs. They make tuning so much easier! I suppose we could say comfort and ease relate to playability-if it hurts to tune, one does not play their instrument! Traditionalists, too, have appreciated the fact that these pegs still look like ebony friction-fitted pegs. You really have to try them out to see just how easy they are to use.

Are you a cellist or interested in becoming one? Take a look at our

Fine Cellos modeled after Stradivari's instruments.

Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The Baroque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07

Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7